|

Pietro

de' Crescenzi, Liber

ruralium commodorum

(The Book of Rural Benefits), 1304-1309

|

The Medieval Almanac

Life on the Farm

By Barunin Gisela

vom Kreuzbach

Gisela.vomKreuzbach@gmail.com

Farming

came to Europe about 11,000 years ago, apparently in two waves from the Middle

East where the science of deliberate agriculture originated. It allowed the

hunter-gatherer peoples who populated the vast European Continent to settle

into permanent stable holdings, villages and, eventually, cities.

In

our period of study agriculture moved from being a matter of mere subsistence

to become the primary economic engine and source of wealth for all of Europe.

Everyone, from the meanest serf to the pope danced to the rhythm of the

seasons.

Coaxing

grain, fruit and vegetable from the thin layer of top soil in the Middle Ages

and Renaissance was a highly labor intensive prospect. At certain times of the

year nearly everyone, save the vicar and the lord of the manor himself, was

involved in producing the best possible harvest. Most of the year, however,

those we would call peasants and serfs worked the land.

Peasants

generally contracted with the local lord for protection and support and farmed

land they might own outright or they owned the rights to in exchange for labor

in the lord’s fields and pastures. It could not legally be taken from them

without good reason based on criminal act or abandonment on the part of the

farmer.

Serfs,

on the other hand, were bound to the local noble by debt of owed labor, rent

and levies. Debt that was, at times, deliberately structured to keep

individuals and their families indentured. Land ownership might be hereditary

but so was debt.

Through

the early part of the Middle Ages in Europe, most land was assigned to manors

of various sizes, generally about 600 acres according to several sources. After

the Norman Conquest there were more than 9,000 such manors in England. Nobles

held at least one, often more, manors.

The

part of Europe that is now Austria, Switzerland, Germany, France and the Low

Countries, had a population that fluctuated between 10 and 15 million from 1 CE

to 600 CE. That more than doubled to 36 million by the 13th Century.

Some attribute the faster growth to the introduction of new, more effective

plow designs that allowed more land to be brought to till. Just to give you an

idea of how sparsely populated the area was at that time, the same area now

supports 250 million.

Farm

yield of the manors was vital to keep the staff and families of the castle,

hall and village fed. Sale of surplus yield and finished goods became

increasingly important as the economies grew. As weather improved, so did

productivity. As the economy and trade strengthened and the population

increased, so did the need for cleared arable land.

More

land and more productivity required more labor. Serfs who owed debt obligations

were cheaper than hired workers or freeholders who sold their goods. It

benefitted the nobility to make it harder to remain a freeholder … a free land

owner and to drive more of the local population into servitude.

“At

the beginning of this period (900 -1200 CE) the main source of wealth was

agriculture, and it remained so throughout. Lords had established their control

over it in much the same way that they had established their rights over men,

amalgamating rights, which had been theirs on their own estates with public

rights and then extending them over as many people as possible within their

lordships. The control of local justice and of obligations to forced labour,

the offer of ‘protection’ and levying of taxation, were the essential means by

which free peasants were reduced to servitude, hereditarily bound to their

tenements and liable to arbitrary levies and labour services. Poor harvests and

flight from marauders were both factors which could lead a freeman to surrender

his liberty, but it was likely that the pressure came from above and was not

willingly conceded from below, because the most rapid subjection of the

peasantry came not in the tenth century, at the time of greatest instability,

but rather in the eleventh when harvests were improving and lords looking for

the means to build in stone rather than wood.” (Holmes, 1988)

This

author illustrates his point by noting that 80% of donations received by the

Chartres cathedral between 940 and 980 were from peasant freeholders. That

figure dropped steadily but slowing until the time of the Conquest when it held

at about 38% for 30 years. Between 1090 and 1130, however, only 8% of donations

to the cathedral were given by free peasants.

The

eleventh-century bishop of Laon called peasants the class that "owns

nothing that it does not get by its own labor and provided the rest of the

population with money, clothing, and food ... Not one free man could live

without them" (Gies & Gies, 1978)

|

| winnowing. |

So

they worked. All of them. From toddling child to elderly grandmother, each

worked at tasks suited to their strengths and limitations.

Men

being, in general, physically stronger than women and unhampered by pregnancy

and small-child care, worked in the fields and forests, clearing land, plowing,

setting fences, building structures, bringing in harvests, shearing sheep and

butchering livestock.

Women

generally kept the home and village, tending livestock and gardens, carding, spinning

and weaving wool, making ale, cheese and butter. At times women helped in the

fields as well, sowing, helping with the harvest scything, tying, and

winnowing.

Children

began to work nearly as soon as they could walk. Very young children would be

stationed in gardens (tofts) and fields (crofts) after planting and sowing to

scare birds away. As they aged, they’d be tasked with climbing to the top of

trees to get the fruit adults could not reach, feeding livestock, tending herds

at pasture, weeding fields and garden plots, gathering wood and helping with

the harvests.

Life

was work. Work was life. There was little distinction made for most people. All

danced to the rhythm of the seasons.

Even

though land was usually allotted to individual families based on seniority,

type and amount of work as well as need, fields were most often worked

communally allowing for larger plots … usually ten times as long as they were

wide which made tasks such as plowing …. And turning a team of oxen … a much

easier endeavor.

Oxen,

some more specialized tools and some larger equipment were generally owned by

the entire village and sometimes were stored in the church.

Fields

were laid out around the village in such a way to contain both good and poor

soil in each. With crop rotation, this gave a greater chance of good harvests

each year.

A three-field system of crop rotation was used

during much of our period in which a plot was sown two years in a row and let

fallow the third to allow the soil to recover. Crops were rotated as it was

long-noticed that if wheat or rye (Wintercorn) followed peas, beans or oats

(Springcorn) the yield was greater. They didn’t understand the cause but today

we know those crops are nitrogen-fixing crops that replenish the nutrients used

by the wheat. During the fallow year fields were fertilized with livestock dung

and marled, a process of spreading clay for the carbonate of lime.

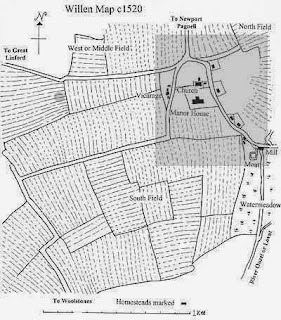

Using

the map of Willen to illustrate, this

year the Middle Field might be sown with winter wheat, the South Field with

oats and the North Field left fallow. Next year the North Field would be sown

with wheat, the Middle with Oats and the South left fallow.

What

type of crops were planted or livestock kept and the timing of agrarian activities

varied from one region to another based on everything from local traditions and

preferences to availability of certain plant and animal varieties to climate

based on elevation or latitude.

Wheat,

rye, barley and oats were fairly ubiquitous as were peas, cabbage, beans and

turnips. Eggplant came from Persia and generally stayed in the warmer climes.

Cattle were widely raised for meat and, in Europe, for milk.

Sheep

were just as widely tended for wool and meat but in the Near and Middle East

sheep and goat’s milk was preferred. Europeans have the genetic ability to

digest cow’s milk into adulthood. Those of Middle Eastern decent tend to lack

the ability and use the much easier digested fermented goats milk.

Barley

was largely used for beer. Rye and wheat for flour and as a cash crop. Hay and

oats generally went for animal feed, though, of course, not always and not

everywhere. A quip from period says, "Oats, food for horses in England,

but men in Scotland," to which the reply was, "Aye, and where do you

find better horses or finer men?"

A

minimum of 36 bushels of wheat (the yield of four acres in an average year) was

required to support a peasant’s family for the year. An acre produced about 7 -

8.5 bushels of grain per acre in Medieval Europe where modern farming methods,

on the same land, yield four times that at 42.5 bushels.

That

yield was only about double the amount of seed used, 4 bu per acre. Barley

would bring about 20 bushels per acre … leaving about 15 after taxes and seed

were pulled … from only 2 bu of seed. Oates yielded a 300 to nearly 400 percent

increase giving 10 -11.5 bu an acre from 3 bu of seed.

Peas,

an important component in the medieval diet across Europe as a protein source,

gave 8.5 - 10 bu per acre from 3 bu of seed.

“Because

of relatively small yields, medieval agriculture was highly sensitive to

adverse weather conditions, both summer droughts, winter freezes, and periods

of overabundance of rain. This meant that a certain level of crop variety was

necessary as insurance against the possible destruction of an important

staple.” (Glick, Livesey and Wallis, 2005)

What

did they grow?

“Sour

and sweet cherries of all kinds, both cultivated and wild, grow in such great

quantity that sometimes it happens that more than sisty carts of them are in

one day brought through the gates of the city, and they are available for sale

in the city at any hour from mid-May until almost mid-July. Plums, too, white,

yellow, dark, damascene, likewise in almost infinite quantity, are distributed

ripe from shortly before the Kalends of July until the month of October.

“At

the same time plums begin to appear, pears, summer apples, blackberries and the

figs named ‘flowers’ appear in abundance; then follow cultivated filberts;

afterwards the cornel-berries, particularly appropriate for ladies; also

jujubes and peaches amazingly abundant; likewise, figs and grapes of various

kinds; also almonds, although few of them; wild filberts, nuts in unbelievable

quantity, which all citizens who like them enjoy all the year round after all

meals. Nuts can also be mixed, ground, with eggs and cheese and pepper to stuff

meat in winter. Also an oil is obtained from them which is liberally consumed

among us. Then again, winter pears and apples and crabapples grow, all of which

abundantly supply our citizens through the winter and beyond. Also pomegranates

appear, most useful to the sick. Grapes of many kinds are abundant, and they

appear ripe about the middle of July and are available for sale until the

Kalends of December or thereabouts.”

Bonvesin

della Riva, On the marvels of the City of

Milan. From the Latin. [1288]

(Lopez

& Raymond 1995)

His

wonderfully descriptive PR letter aside … crops generally produced in most of

Europe in our period were:

Peas,

lentils, fava beans, cabbage, onions, shallots, leeks, garlic, herbs, carrots,

beets, turnips, rutabagas, parsnips, greens, parsley, chickpeas, navy beans, wheat,

rye, barley, oates, millet, flax, hemp (for ~fiber~), apples, pears, cherries

(sweet and sour), olives, figs, quinces, mulberries, walnuts, chestnuts, (Warmer

climes had almonds, peaches, plums and in Italy and Spain, citrus)

Sheep,

cattle, goats, chickens, pigs, horses, oxen

After

the Muslim conquests in the East during the 8th and 9th

Centuries techniques and cultivars from the Subcontinent such as rice, sugar

cane, citrus fruits and cotton were appropriated throughout the Islamic world.

Crops cultivated in monsoon conditions, in Europe had to be irrigated.

Something the Arabs called “Indian Farming” (filaha hindiyya). As these

techniques and crops spread through Persia toward Europe, they picked up

Persian cultivars … eggplant and artichokes.

And

so it continued until today, new technologies, and new varieties

increasing our access to food and our enjoyment of it.

14th

C English Poem

Januar: By

thys fyre I warme my my handys

Februar: And with my spade I delfe my landys

Marche: Here I sette thynge to sprynge

Aprile: And here I here the fowlis synge

Maii: I am as lught as burdie in bowe

Junii: And I wede my corn well mow

Julii: With my sythe my mede I mowe

Auguste: And here I shere my corne full lowe

September: And with my flaylle I erne my brede

October: And here I sawe my whete so rede

November: At Martynesmasse I kylle my syne

December: And at Chritemasse I drynke redde wyne

Winter

JANUARY

Repairs to tools, buildings, fences, Some planting of early

vegetables such as peas and onions depending on locale, Weaving, Crafting new

tools, baskets, rope, nets, leather straps, Pruning Mature Trees, Clearing

ditches, cutting wood, breeding sows, spreading fertilizer, early lambing

FEBRUARY

Plowing in Southern lands, Planting, Fertilizing and

amending soil with chalk and lime, Repairs, Clearing new fields, Pruning fruit

trees and stalking vines, Lambing, Mending fences, Planting willows, Lambing,

Calving

Spring

MARCH

Spreading Manure, Plowing, Planting early vegetables

depending on locale, also flax and hemp, Sowing (scattering seeds in large

fields such as grains for fall harvest and hay), Harrowing, Calving, Pruning

Vines, Lady Day, March 25 marked the unofficial beginning of the new year for

many as this day was the mile marker for returning to the fields.

APRIL

Pruning Young Trees to encourage stronger more productive

growth, Weeding, Scaring Birds, Planting pulses (peas and beans), cabbages,

onions, carrots, parsnips, beets, leeks, turnips. Orchard Trees, Harrowing,

Household gardens would have been planted in this time with sage, basil, thyme,

rosemary, fennel, Parsely, dill, mint,chives, daisies, dandelion, wormwood,

nettle, primrose, rocket, spinach, lettuce, cress, borage, rocket. Weaning

calves, Dairy work comes into full swing, Farrowing piglets

MAY

Weeding, Scaring Birds, Planting New Trees, Gathering Early

crops such as cherries, strawberries, Digging Drainage Ditches, First plowing

of Fallow fields, Capturing new swarms of bees, Mark sheep, Plant garden

vegetables and pulses in cooler climes, Roof thatch repair begins

Summer

Wash and Shear sheep, Harvesting (two main harvests, hay, barley,

vetches, oats, peas, beans in late spring - early summer, wheat, rye and grapes

late summer. If a spring grain crop was planted then another grain harvest in

late fall), Weeding, Shearing Festsival

JULY

Shearing continues, Hay Mowing continues, Harvest of winter

crops continues, Plowing harvested fields and marled fallow fields under,

Gathering berries, Weeding, Harvesting flax and hemp, Washing, Carding and

Spinning the wool, Gathering Wood a nearly year-round task to ensure enough

fuel for winter as well as resources to craft tools, fences and repair buildings

AUGUST

Harvesting Grain (winter crop in cooler climes) and hay,

Tying sheaves and storing for threshing and winnowing later, Washing, Carding

and Spinning the wool, Plant turnips

SEPTEMBER

Harvesting grains (spring crop), Honey and wax, peas,

apples, pears, blackberries and grapes, Breeding cattle, Tying, Threshing,

Winnowing, Milling (The first record of a windmill in England was 1185 in Yorkshire.

Shortly afterwards, Pope Celestine III declared the air used by windmills was

owned by the church and so a tax must be paid to the church for their use.), Plow

fields for winter grain planting, Sow winter grain, Washing, Carding and

Spinning the wool, Pruning Fruit Trees, Harvest Festival, Sell excess livestock

OCTOBER

OCTOBER

Last Plowing, Tilling, Harrowing, Sowing winter wheat, oats

and barley, Milling, Weaving, Carding and Spinning the Wool, Brewing, Drive

pigs to forage on Acorns and beechnuts, Harvesting Grapes and begin production

of wine and verjuice, Breed sheep.

"About nones on 2 Oct., 1270, Amice daughter of Robert Belamy of

Staploe and Sibyl Bonchevaler were carrying a tub full of grout between them in

the brewhouse of Lady Juliana de Beauchamp ... intending to empty it in a

boiling leaden vat, when Amice slipped and fell into the vat and the tub upon

her ... the household came and found her scalded almost to death. A chaplain

came and Amice had the rites of the church and died by misadventure about prime

the next day" (Amt, 1993, p. 189).

NOVEMBER

Butchering begins (Nov. 11, St. Martins Day),

Salting/Smoking Preserving, Weaving, Gathering Willow and Reed for weaving

baskets, Gathering Acorns for pigs feed, Gathering fuel wood for winter,

Threshing and Winnowing, ideally suited to rainy and cold days, comes into full

swing.

DECEMBER

Butchering, Salting/Smoking Preserving, Weaving, Gathering

Willow and Reed for weaving baskets, Digging drainage ditches, Graves, Solstice

and Christmas Celebrations

Bibliography

Amt, E. (Ed.) (1993). Women's Lives in Medieval Europe. New York and London: Routledge.

Balter, M. (2011) Farming conquered Europe at Least Twice. Science Magazine 31May 2011

Gies, F. and Gies, J. (1978). Women in the Middle Ages. New York: Harper Perennial.

Glick, T., Livesey, S.J. & Wallis, F. (2005) Medieval Science, Technology And Medicine: An Encyclopedia. New York: Rutledge

Goldberg, P.J.P. (Ed.) (1995). Women in England c. 1275-1525. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press.

Hanawalt, B.A. (Ed.) (1986). Women and Work in Preindustrial Europe. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Hartman, R. (2001) The Medieval Agricultural Year, http://strangehorizons.com/2001/20010212/agriculture.shtml

Holmes, George (Ed.) (1988). The Oxford Illustrated History of Medieval Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Lopez, R.S. & Raymond, I.W. (1995). Medieval Trade in the Mediterranean World: Illustrative Documents Translated with Introductions and Note. New York: Columbia University Press

Staples, A. (2011) The Medieval Farming Year. http://www.penultimateharn.com/history/medievalfarmingyear.html